My idea of Unified Notation is something very hard to even imagine. The heart of this idea is to have a Dynamic Medium with paper-like capabilities; by which I mostly mean the included freedom. There is a huge gap between a “Tool” and its “Creation”. The paper gives you a canvas and you may bring any tool of your liking so that you can modify this paper.

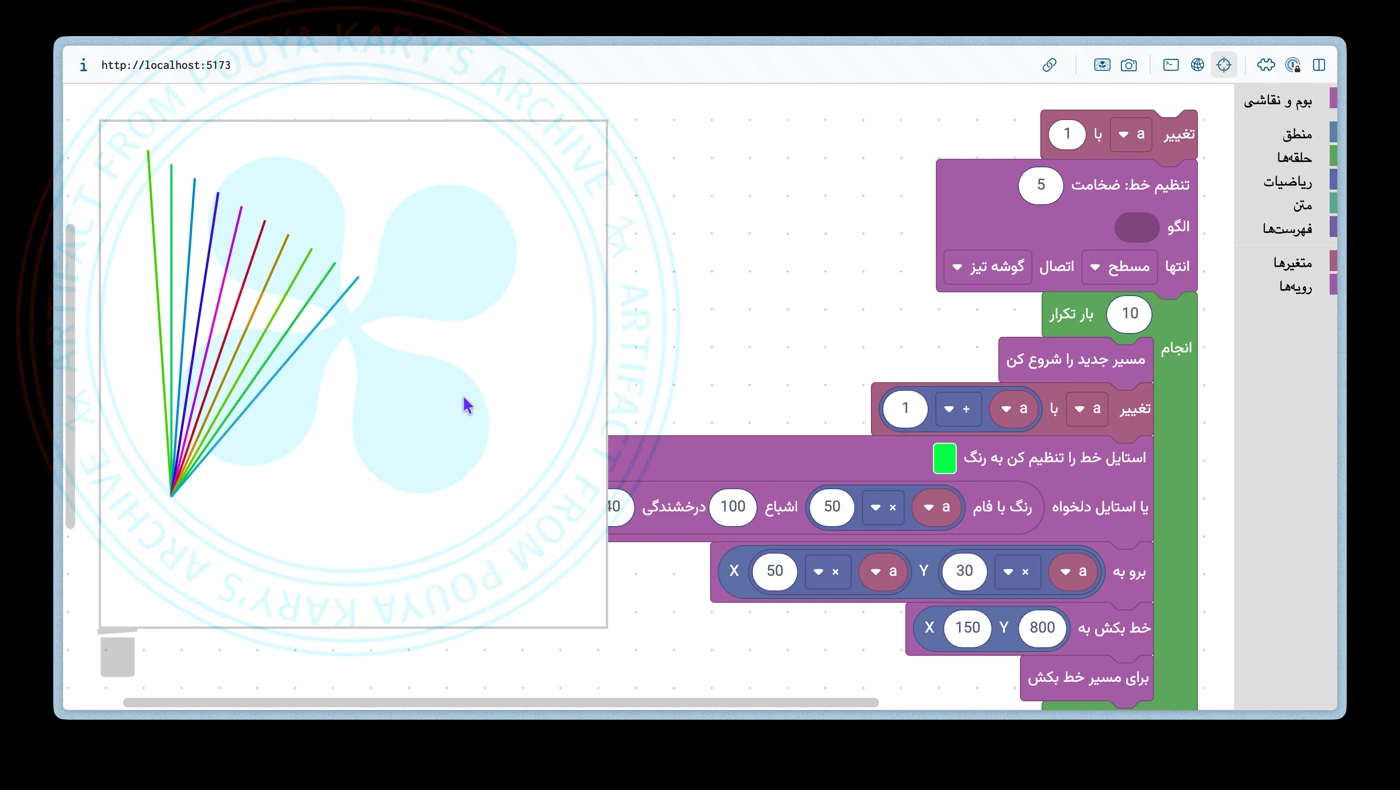

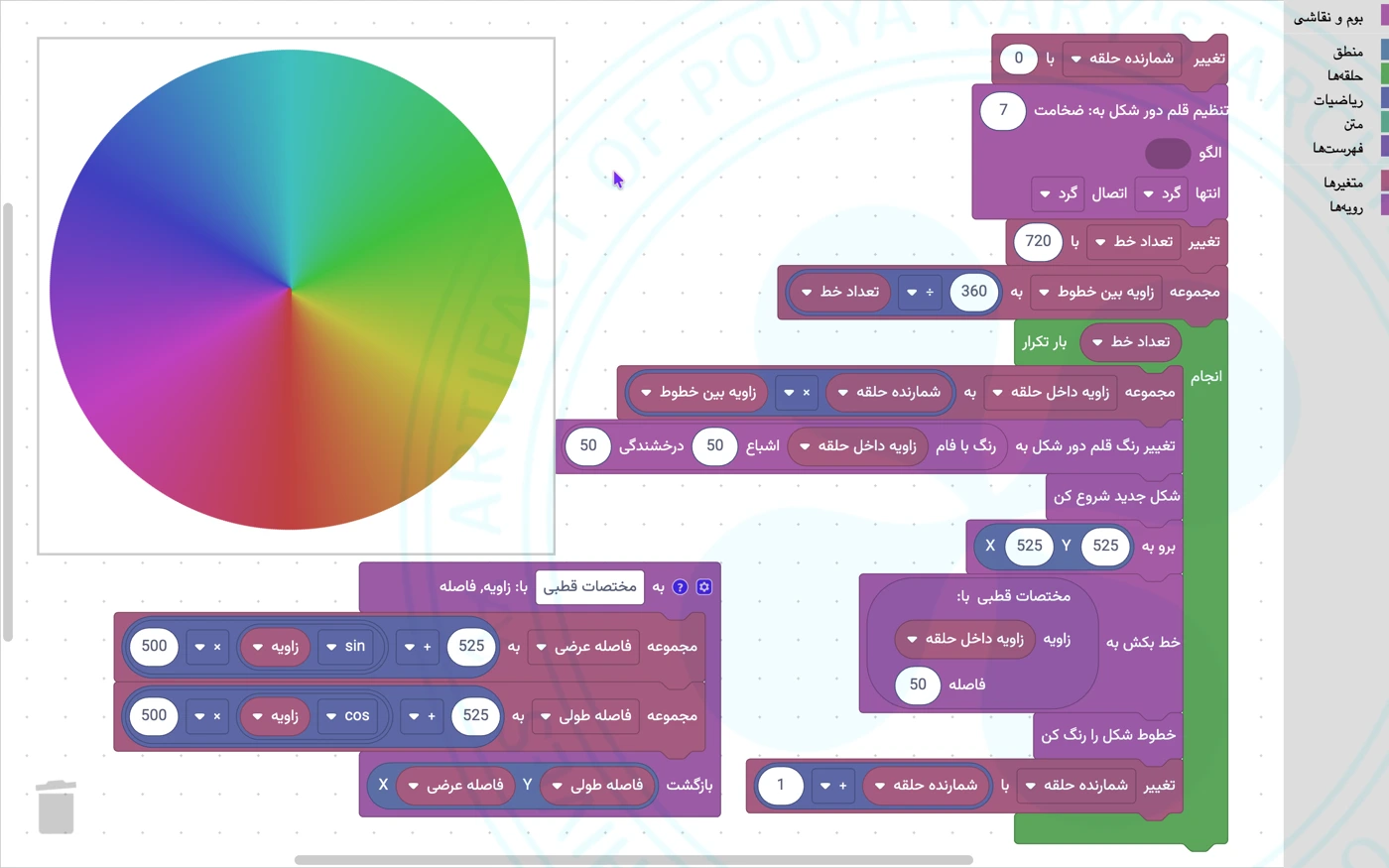

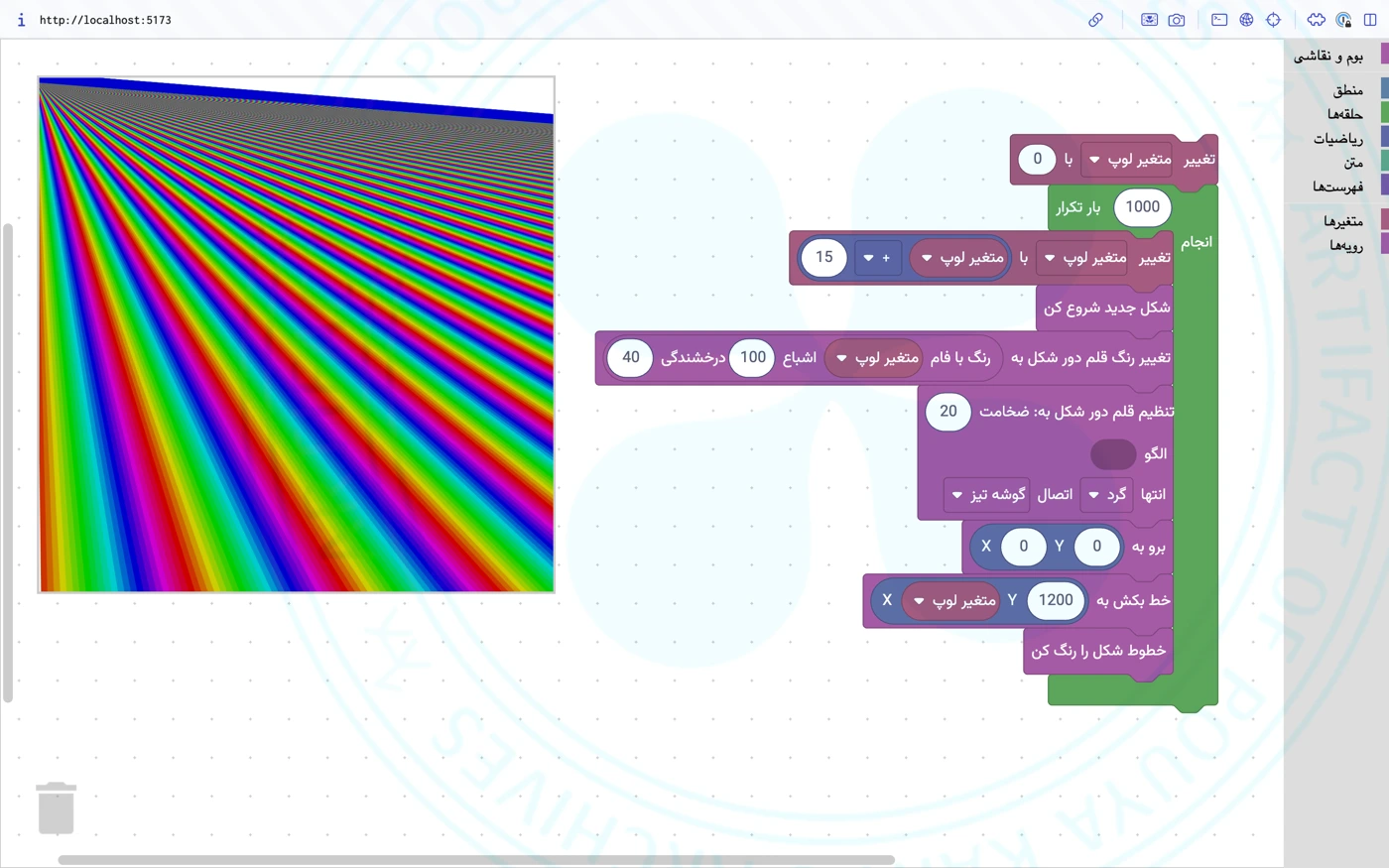

When it comes to a computer, things become even more simple: you have a 2D matrix of colors, and however you change the matrix is a way. Some people simply modify it, some go the long way to create mathematical paths and render vectorized things; some go to the GPU; some load pictures. Yet, at the end, it will be manipulating a matrix. Now let us move further and examine this whole differently. And so the problem remains to be the one I have always been grappling with; the problem that:

In Dynamic and Immutable media, the look might perhaps be the same; but between them there lies an ocean of difference.

The brain “sees” an immutable picture of a Medium and somewhere in that brain the Medium gets interpreted. And therefore there is no difference in how the information was constructed—or, more importantly, if the “Pen” knew what it was painting.

The same can not be told of the Dynamic Media. One can not say that there is no need for a calculator to actually know what it is doing. Quite the contrary; the calculator has to know exactly what it is doing; otherwise it is not calculating. One can say that dynamic media are essentially—as they always have been—deceptions: machines that emulate reality. The way Bret Victor 🞶 calls it: Simulation. These media have always naturally been islands of rare existence.

The communication between a dynamic Medium and a person happens by a machine, rapidly thinking the way a person must think; simulate imaging that creates the illusion of a paper medium and transmits it to the brain in the hope that the brain gets the same image.

What has come out of this—which is the result of a perhaps competing industry—can be seen as isolated images. Because, while they look the same to a brain, underlying are fairly different, incompatible machines. It can be said that it has not been the vision. People at XEROX PARC had such amazing things in SmallTalk that, if realized, this whole idea might have been very different in the “production” mode: a mode in which one could have shared the logic of creating all of these simulating machines.

But still, to have a full notation system it could not have been enough. Because while it could share the button logic, it could not have connected Musical Notation to Math. This is perhaps the biggest advantage of having a mind that interprets.

The way I have so simply annotated this image, in its most basic form, is either impossible for a computer or, if possible, meaningless.

However, there is a fairly interesting thing that came to my mind today. What if we had a system that allowed arbitrary data and annotations to be made, and had an engine that could select an interpreter by type. Say:

MATH AST → Symbolic, Expanded Math AST Musical Notation AST → Rendered Sound Musical Notation AST → Mathematically Annotated Musical AST

And the system could query engines and compose a combination of them? This is me improvising on the idea and it is perhaps not even meaningful; but then what if languages could be partial, and a meta-notation was a system configuring a “Field Language” and “Interpreter” based on the data?

I have to sleep on this and think what I’m thinking.

<drawing> The document consists of five handwritten pages in teal ink on light dotted paper, mixing text and simple line drawings.

Page 1: No drawings, only text. Title is centered at the top, larger and more decorative. Body text is left-aligned paragraphs discussing “Unified Notation,” dynamic media, and matrices of colors.

Page 2: At the top, a horizontal line of text about “Dynamic and Immutable media.” Below it, in the middle of the page, there is a visual comparison between a person looking at a static picture and tools drawing on paper. On the left, a simple outline of a human head faces a rectangular “picture” or “screen,” with an arrow from the head to the picture, indicating perception. On the right, there is a small pen-cup or tool holder containing brushes or pens, next to an oversized pencil drawing on a sheet of paper. Under these drawings, there are two caption blocks separated by dashed horizontal lines: the left caption talks about the brain seeing an immutable picture that gets interpreted; the right caption mentions that there is no difference in how the information was constructed and imagines a “pen” that knows what it is painting. At the bottom of the page, there is a block of prose text about calculators, dynamic media, deceptions, and simulation.

Page 3: At the top, the prose continues from the previous page, ending in “As:”. Beneath that, there is a large diagram showing the chain of communication between hardware, a dynamic medium, and a human. On the left, there is a small square computer-chip icon with pins on its sides. An arrow points from the chip to a laptop drawn in simple perspective, with a visible screen and keyboard. From the laptop, two arrows go to the right: one arrow ends at a simplified outline of a human torso and head (the “person”), and above that, another arrow continues to a more abstract head-like shape representing the “brain.” A return arrow loops from the brain back toward the laptop/chip side, suggesting a feedback loop. Under this diagram, a caption explains that a machine rapidly simulates a paper medium and transmits its image to the brain. Beneath the caption, another block of text discusses incompatible machines, XEROX PARC, Smalltalk, and a “production mode” where logic of creation could be shared.

Page 4: Mostly text, with one musical example. In the upper half, paragraphs talk about simulating machines, notation systems, and connecting musical notation to math. In the lower left quadrant, there is a short fragment of musical notation: a five-line staff with a treble clef and a small group of notes, including a beamed figure; under the staff, there is a “2/2” or similar time-signature-like mark. To the right of the staff, a caption states that this simple annotation is either impossible or meaningless for a computer. Below, the text introduces the idea of a system that can attach arbitrary annotations and choose interpreters by type. Near the bottom, three short lines show type-transform arrows: “MATH AST” to “Symbolic, Expanded Math AST,” “Musical Notation AST” to “Rendered Sound,” and “Musical Notation AST” to “Mathematically Annotated Musical AST.”

Page 5: Only handwriting, no drawings. A single centered paragraph continues the idea of querying engines and composing combinations of interpreters, improvising on partial languages and a meta-notation that configures a “Field Language” and “Interpreter” based on data. At the bottom, a closing line says the author has to sleep on the idea and think about what they are thinking. </drawing>