Upon visiting a restaurant days ago, I saw my favorite cat there (whom I used to see every time I visited) and this time she missed a leg. It was so horrible to watch. She was doing all her best to walk with three legs. The memory of that instance is haunting me everywhere.

First action towards military service taken. I hope not to die, but more, I hope not to be disturbed from a good work.

This is the 1800th day of Zea 🞶 and I. Such a strange feeling that we have stayed together this long.

When designing a space, I find it paralyzing to add lights. By the addition of each single light, everything changes: every color, every atmosphere that was previously designed with such care, all the senses and feelings—each of them must be considered anew, as if the room had never been thought about before. In his seminal paper, Five Things We Need to Know about Technological Change, Dr. Maestro Postman 🞶 so wisely observes what has long resonated with me:

Technological change is not additive; it is ecological. I can explain this best by an analogy. What happens if we place a drop of red dye into a beaker of clear water? Do we have clear water plus a spot of red dye? Obviously not. We have a new coloration to every molecule of water. That is what I mean by ecological change. A new medium does not add something; it changes everything. In the year 1500, after the printing press was invented, you did not have old Europe plus the printing press. You had a different Europe. After television, America was not America plus television. Television gave a new coloration to every political campaign, to every home, to every school, to every church, to every industry, and so on.

I hope you forgive my vanity in saying that I cherish this shared observation, as I find it to be a bond between me and Dr. Postman: a small bridge of intuition across time. Today, however; I believe there is more to be added to it—not in contradiction, but as a kind of extension into the late twentieth and early twenty-first century condition in which we now live.

Walking past a street one day, I found myself thinking about Aaron Swartz. From there my thoughts wandered, as they often do, to the manner in which the world has become fragmented: splintered into domains, issues, and crises, such that each activism is compelled to operate upon a tiny piece of this grand fragmentation, rarely able to see, let alone to address, the totality. The interesting thought that arose immediately after was this:

How do so many problems occur in nature? Perhaps, in their primordial form, a problem is a tiny disturbance happening in a strictly local portion of the world, not affecting other portions at all. What happens if a dog is mean to a cat? One thing we can say, with some confidence, is that the rest of the world will not be suffering from it.

Within the older, slower ecologies of nature, most troubles are local. They may be cruel, they may be tragic, but they are, in an important sense, bounded. But now imagine the world in which you and I actually coexist. We inhabit not a loose scattering of local ecologies but a gigantic system of interconnected humanity in the post–twentieth-century era—a world whose fibers have been densely woven by electricity, computation, and global industry. In such a world, the surveillance efforts of the United States, the microplastics released from Teflon, the Chernobyl disaster: none of these remain local events. They are, in different ways, diffused into the very air, the waters, the politics, the bodies of almost everyone; they become, in varying degrees, the shared inheritance of the species.

If we return to the problem of adding lights, or to Postman’s ecological change, we soon realize that our complex system appears to live at—or perilously near—a saturation level of problems. If you experiment in thought with a single drop of ink falling into a clear liquid, it is easy enough to discern what has changed. But now imagine adding multiple colors, drop after drop, every second, without pause. At a certain moment, the entire system becomes so saturated that it becomes impossible even to distinguish between the effects of the different problems; everything is simply, and irreversibly, colored. Perhaps that is Maestro McLuhan 🞶’s allatoneness—his “all-at-once-ness”—actually happening, and it surely can be referred to as such: a condition in which every new intervention enters a medium already thick with prior consequences.

The dystopian turn of ecological change, then, lies in the contrast between natural and technological agency. Within nature, the effect of a natural agent—such as a cat, a dog, even a small predator—is fairly limited by the structure of the ecosystem itself. But our democratization of tools is steadily enabling each individual human being to have an impact at something closer to the size of the world, and that, to me, is a hugely frightening scene to imagine—only to realize that it is not merely imagined, but in fact being lived, day by day, update by update, device by device.

Maestro Kay 🞶 has remarked many times that “once you have something that grows faster than education grows, you’re always going to get a pop culture.” What keeps me awake at night is precisely a world configured in this manner: a world in which almost no person is acquainted with the philosophical thoughts of creation, no person schooled in the deep responsibilities of making, and yet everyone is given, or soon will be given, the possibility to change everything.

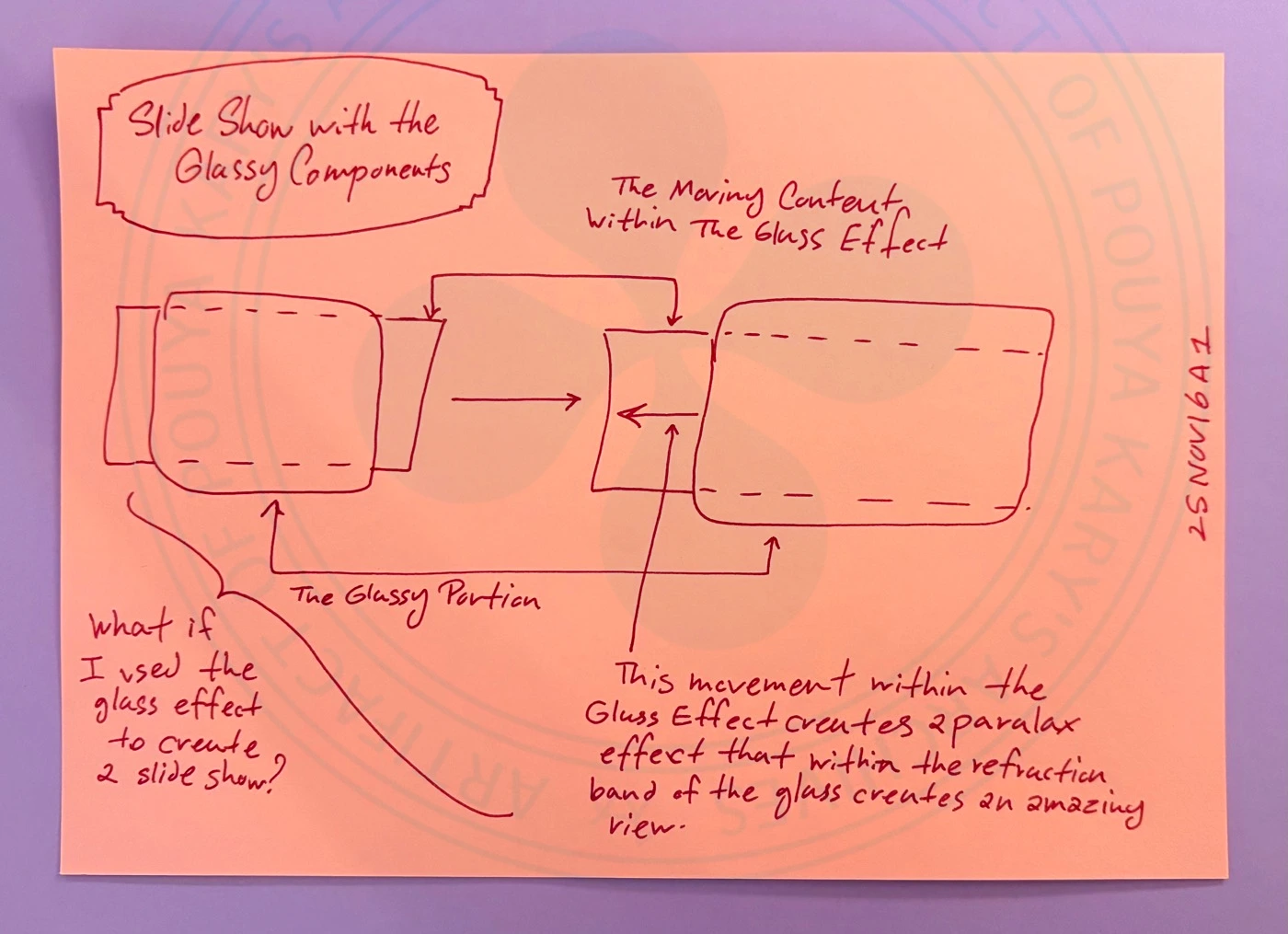

Ideas for using the Glass Distortion Plane of AnnotationsKit (1/4)

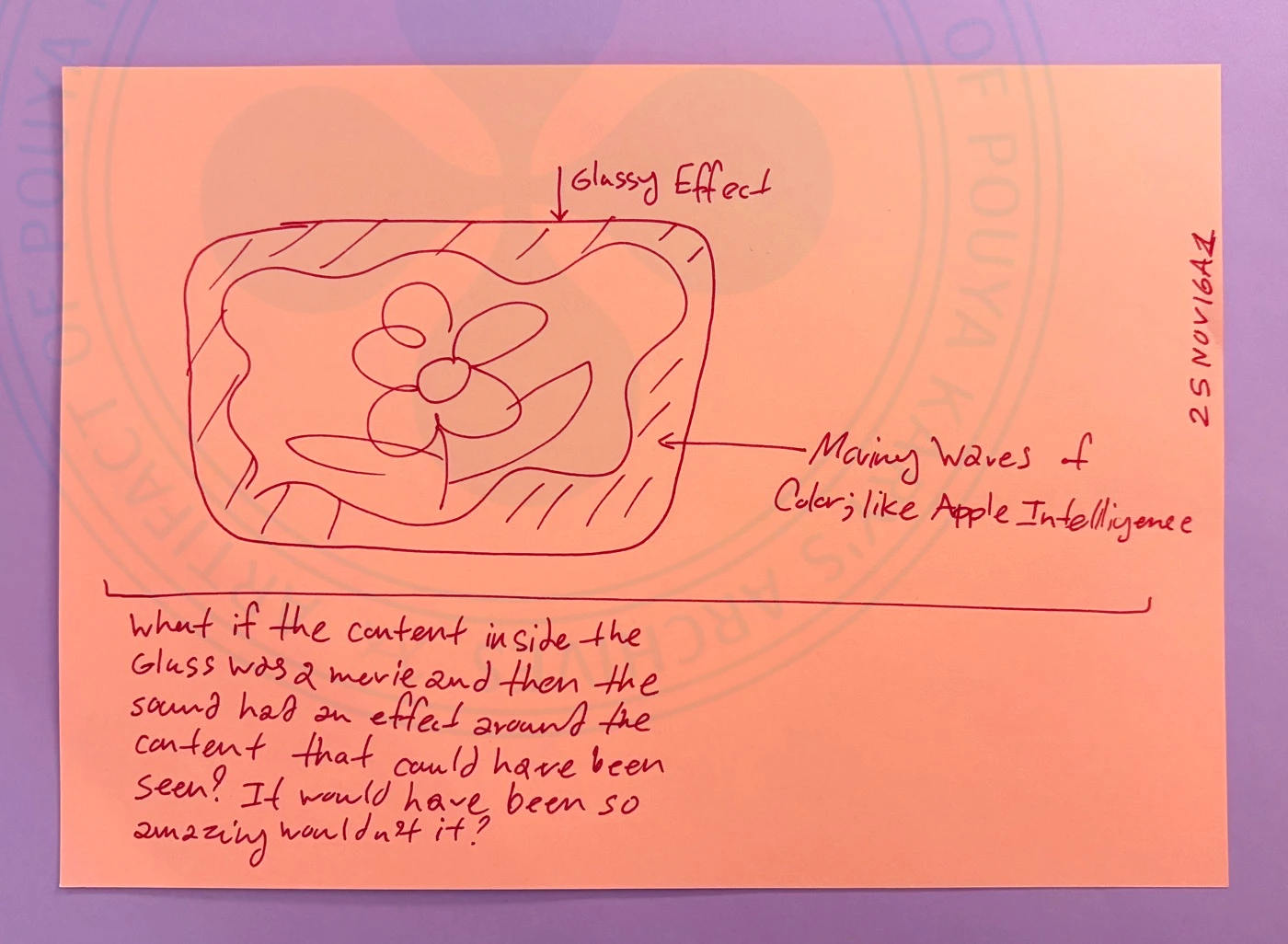

Ideas for using the Glass Distortion of AnnotationsKit (2/4)

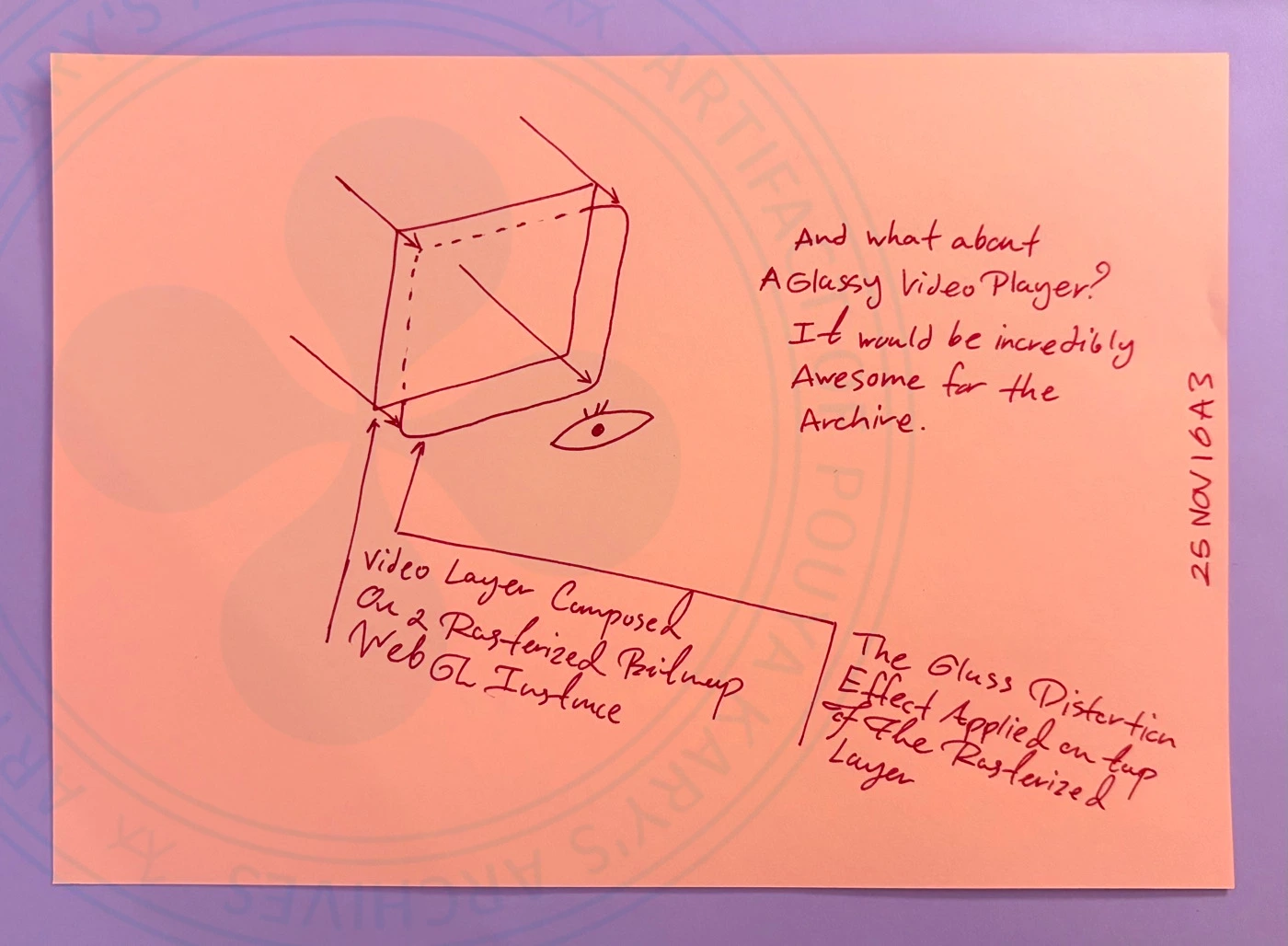

Ideas for using the Glass Distortion of AnnotationsKit (3/4)

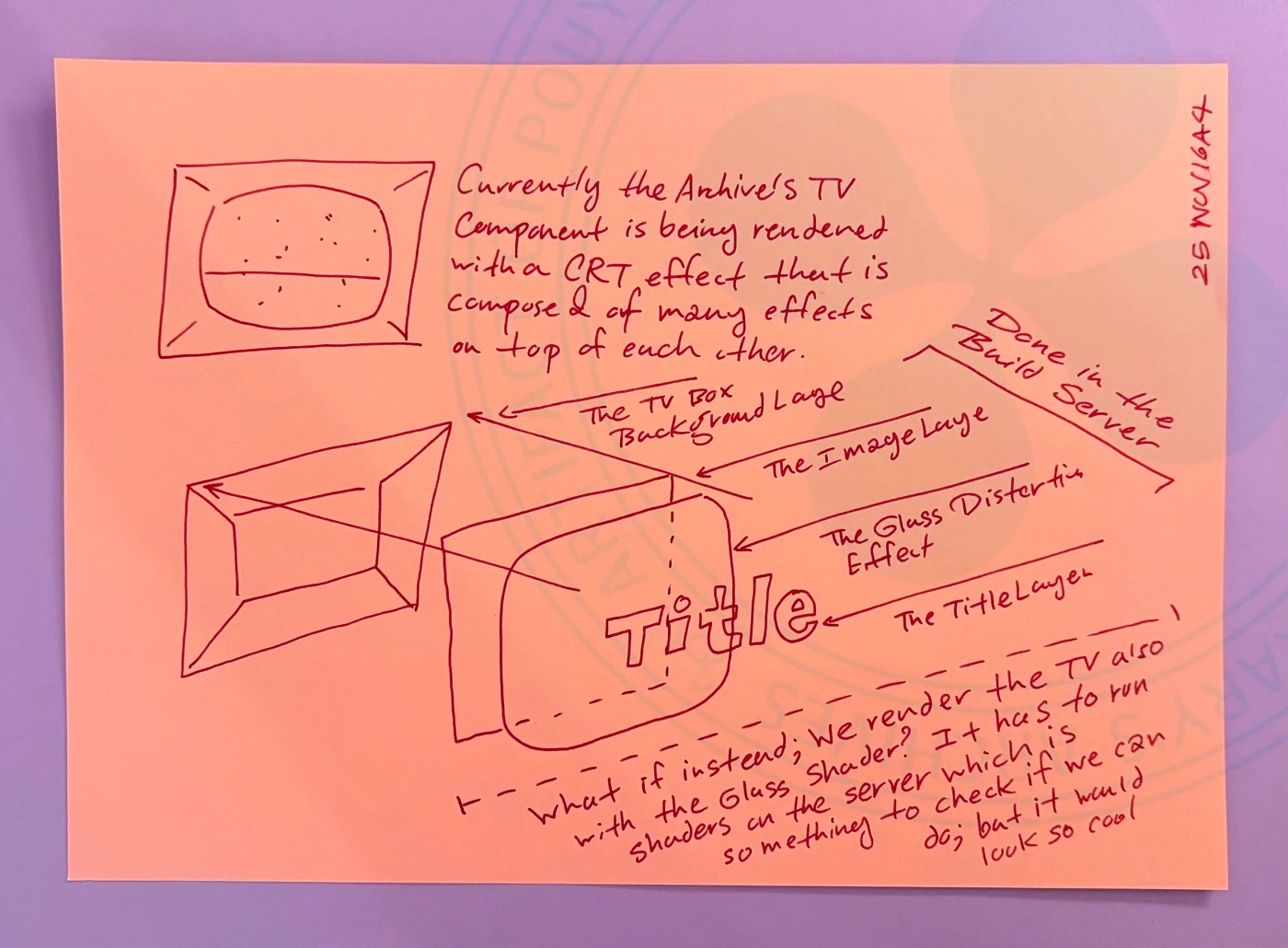

Ideas for using the Glass Distortion of AnnotationsKit (4/4)

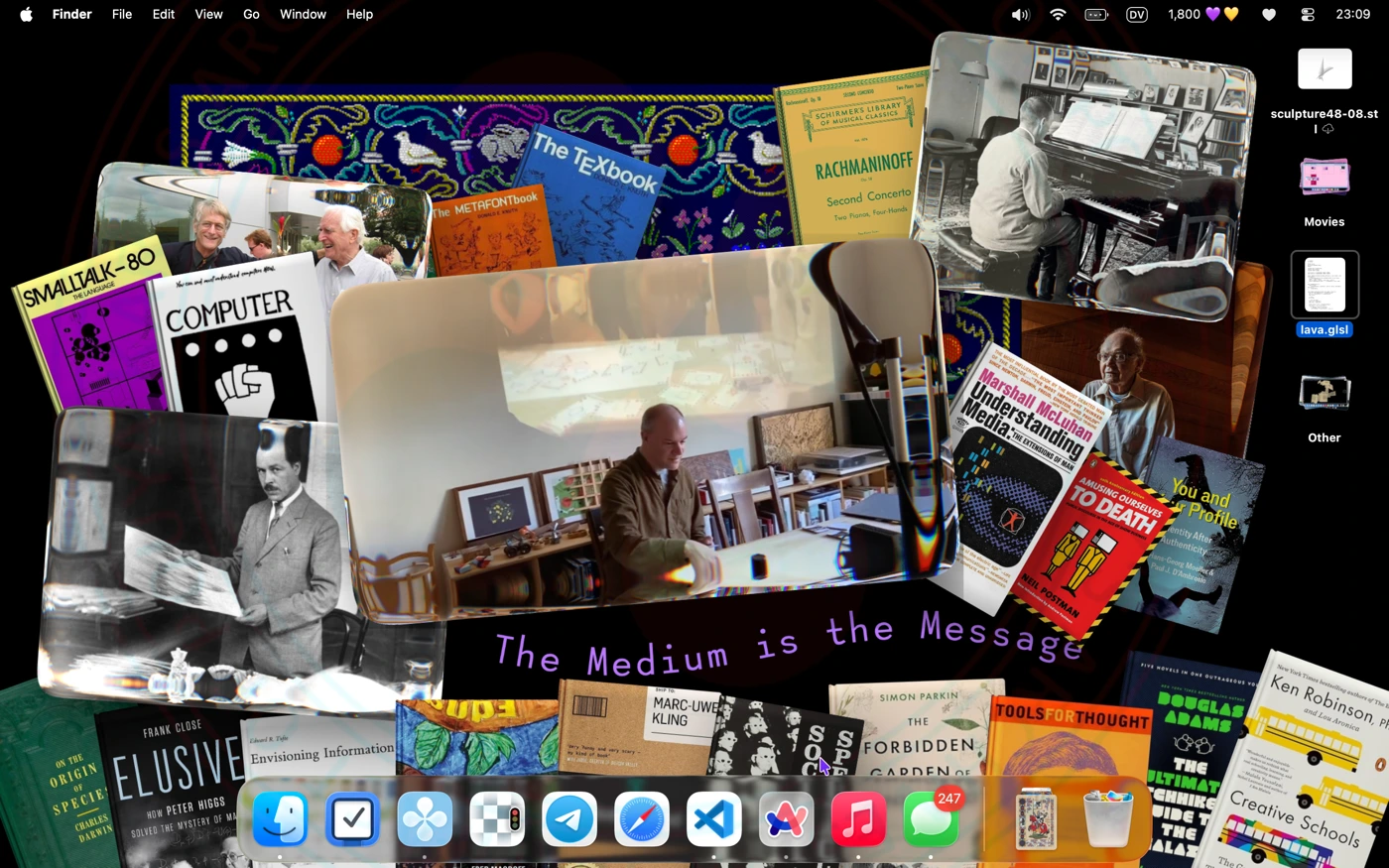

Modifying my inspiration’s wallpaper: Added Computer Lib and Maestro Knuth 🞶. Also added some books to the bottom for Dock to look better. (1/1)