When you read a book like Maestro Postman 🞶's books, so many things repeat and repeat. Some dismiss this as useless repetition, but this is actually muscle memory in the brain. Reading something over and over so much that it exhausts you means you have internalized it.

When I don't give LLMs context, they don't understand what I say. When I provide such a thing, it makes them protect me so much that they don't mention my faults, and I embarrass myself.

Ashkan Bonakdar 🞶 told me that he has this sheet where he collects the behavior of some actors and then asks an LLM to predict next actions. He says that it almost always correctly predicts that you may encounter X at time Y. I think single handedly this is the most brilliant and genius use of these tools. Not event the best organizations in the whole world have understood the nature of these things as good as he has.

And that is exactly why I am both so proud and so pleased to be working with Ashkan Bonakdar 🞶. He really is a human in size of Bob Taylor 🞶 and J.C.R. Licklider 🞶.

I believe in my work, but act as if it is not my belief.

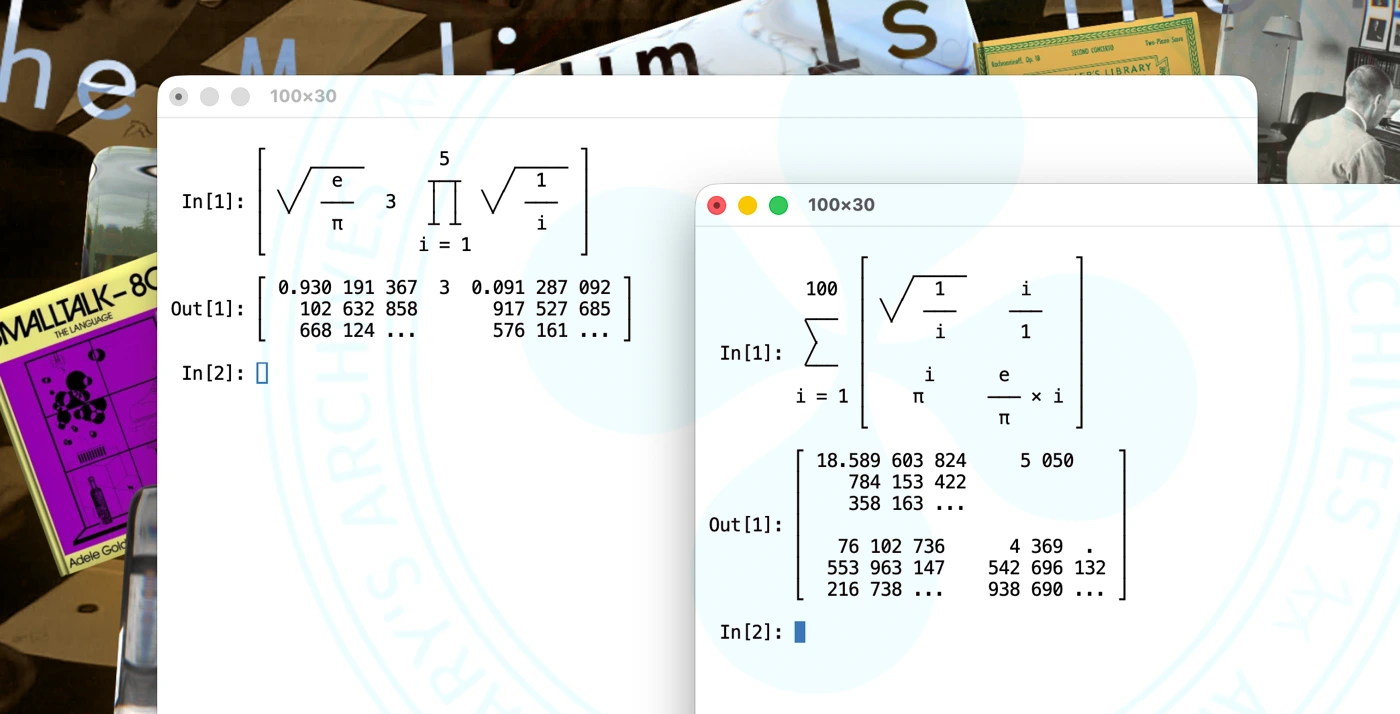

Today, It turned out that certain instances of combining the matrix grammar in Nota Language 🞶 will result in total breakdowns. Fortunately, these issues have been resolved, but this revelation has left me apprehensive. Its grammar has been consistently sound for quite some time, and I had almost assumed it required no further attention. (1/1)

Maestro Babbage 🞶 and Herschel started a project to produce tables for their new Astronomical Society, and it was in the effort to check these tables that Babbage is said to have exclaimed, “I wish to God these tables had been made by steam!”—and began his lifelong effort to mechanize the production of tables.

Maestro Babbage 🞶 had them printed on yellow paper on the theory that this would minimize user error.

Maestro Lovelace 🞶's father Lord Byron said he gave her the name “Ada” because “It is short, ancient, vocalic”.

Maestro Babbage 🞶 seems at first to have underestimated Maestro Lovelace 🞶, trying to interest her in the Silver Lady automaton toy that he used as a conversation piece for his parties (and noting his addition of a turban to it). But Ada continued to interact with (as she put it) Mr. Babbage and Mrs. Somerville, both separately and together. And soon Babbage was opening up to her about many intellectual topics, as well as about the trouble he was having with the government over funding of the Difference Engine.

When Maestro Lovelace 🞶 was 11, she went with her mother and an entourage on a year-long tour of Europe. When she returned she was enthusiastically doing things like studying what she called “flyology”—and imagining how to mimic bird flight with steam-powered machines.

Maestro Lovelace 🞶 had gotten to know Mary Somerville, translator of Laplace and a well-known expositor of science—and partly with her encouragement, was soon, for example, enthusiastically studying Euclid.

Maestro Lovelace 🞶 wrote to her mother: “I believe myself to possess a most singular combination of qualities exactly fitted to make me pre-eminently a discoverer of the hidden realities of nature.”

Though often distracted, Maestro Babbage 🞶 continued to work on the Difference Engine, generating thousands of pages of notes and designs. He was quite hands on when it came to personally drafting plans or doing machine-shop experiments. But he was quite hands off in managing the engineers he hired—and he did not do well at managing costs.

Maestro Lovelace 🞶’s parents were something of a study in opposites. Byron had a wild life—and became perhaps the top “bad boy” of the 19th century—with dark episodes in childhood, and lots of later romantic and other excesses. In addition to writing poetry and flouting the social norms of his time, he was often doing the unusual: keeping a tame bear in his college rooms in Cambridge, living it up with poets in Italy and “five peacocks on the grand staircase”, writing a grammar book of Armenian, and—had he not died too soon—leading troops in the Greek war of independence (as celebrated by a big statue in Athens), despite having no military training whatsoever. Annabella Milbanke was an educated, religious and rather proper woman, interested in reform and good works, and nicknamed by Byron “Princess of Parallelograms”. Her very brief marriage to Byron fell apart when Ada was just 5 weeks old, and Ada never saw Byron again (though he kept a picture of her on his desk and famously mentioned her in his poetry). He died at the age of 36, at the height of his celebrityhood, when Ada was 8. There was enough scandal around him to fuel hundreds of books, and the PR battle between the supporters of Lady Byron (as Ada’s mother styled herself) and of him lasted a century or more.