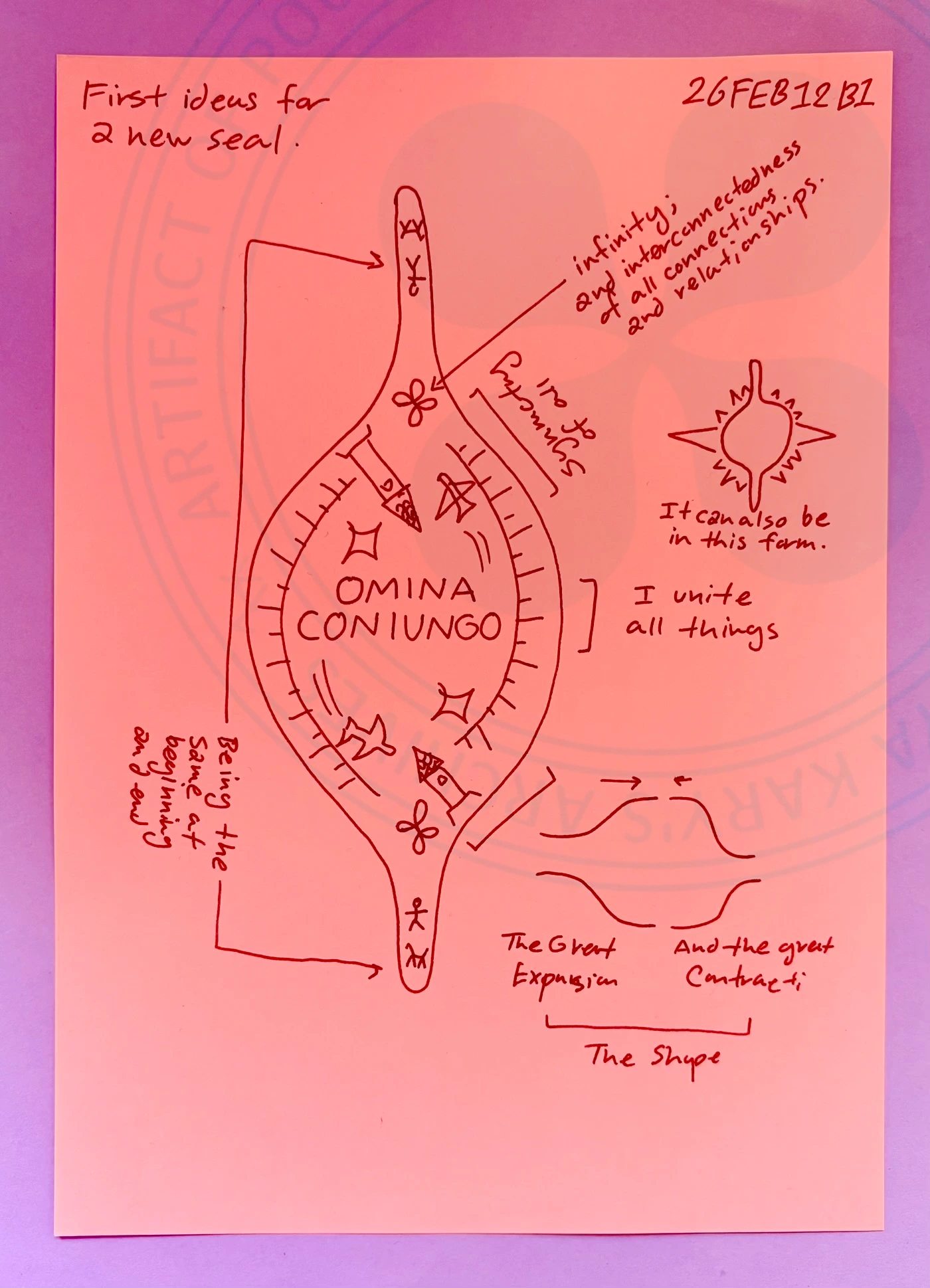

First Ideas For A New Seal (1/3)

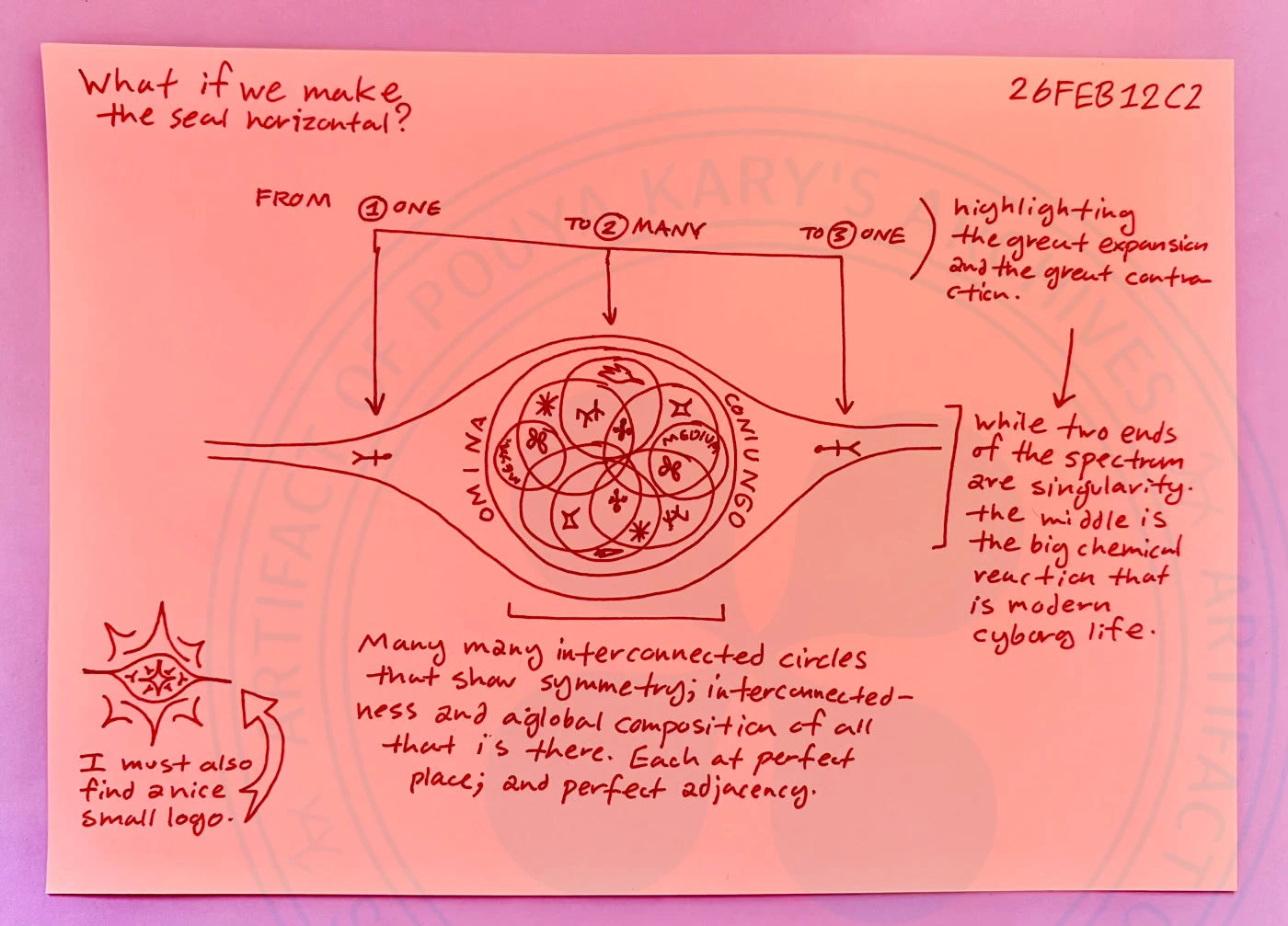

First Ideas For A New Seal (2/3)

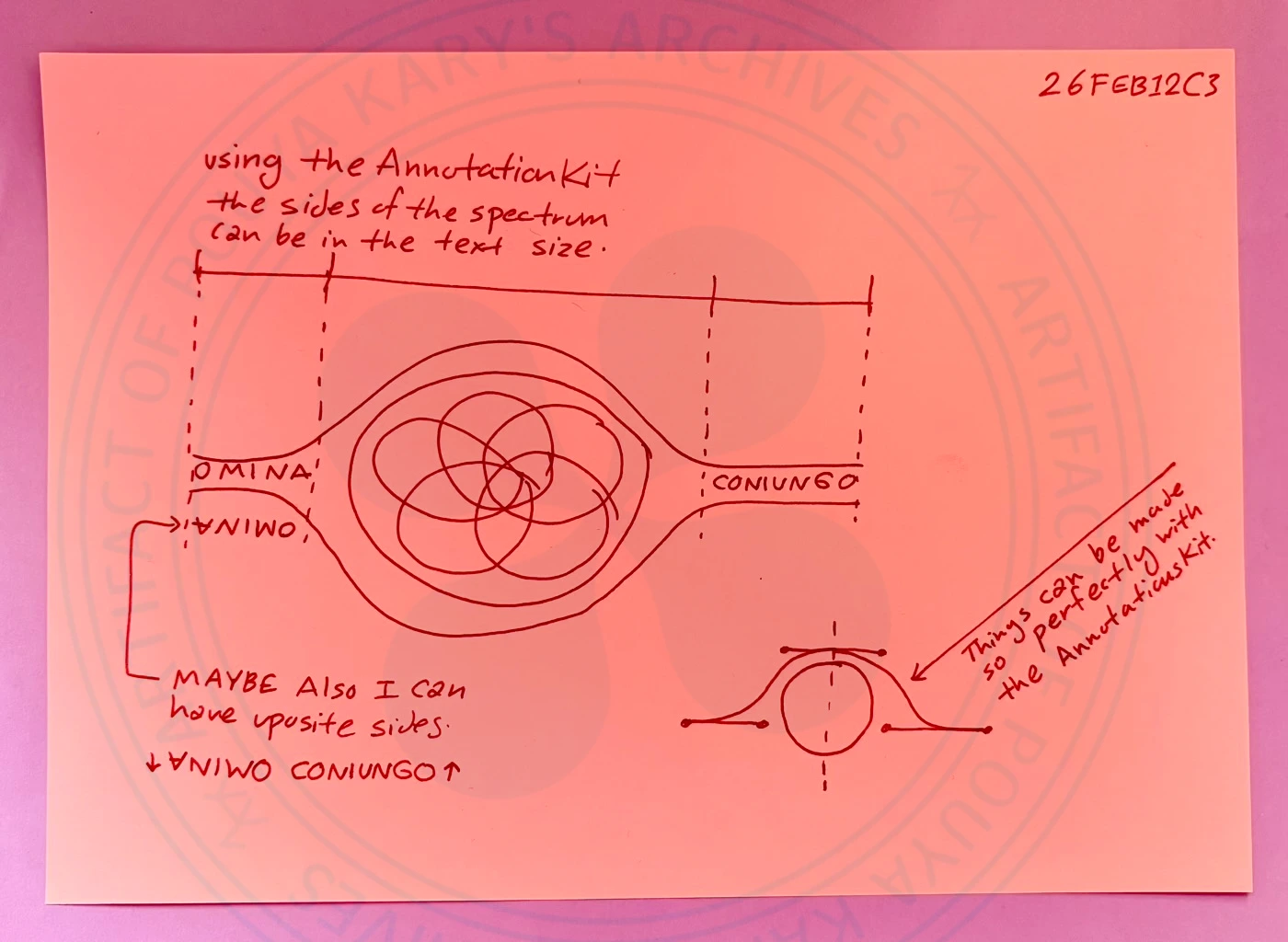

First Ideas For A New Seal (3/3)

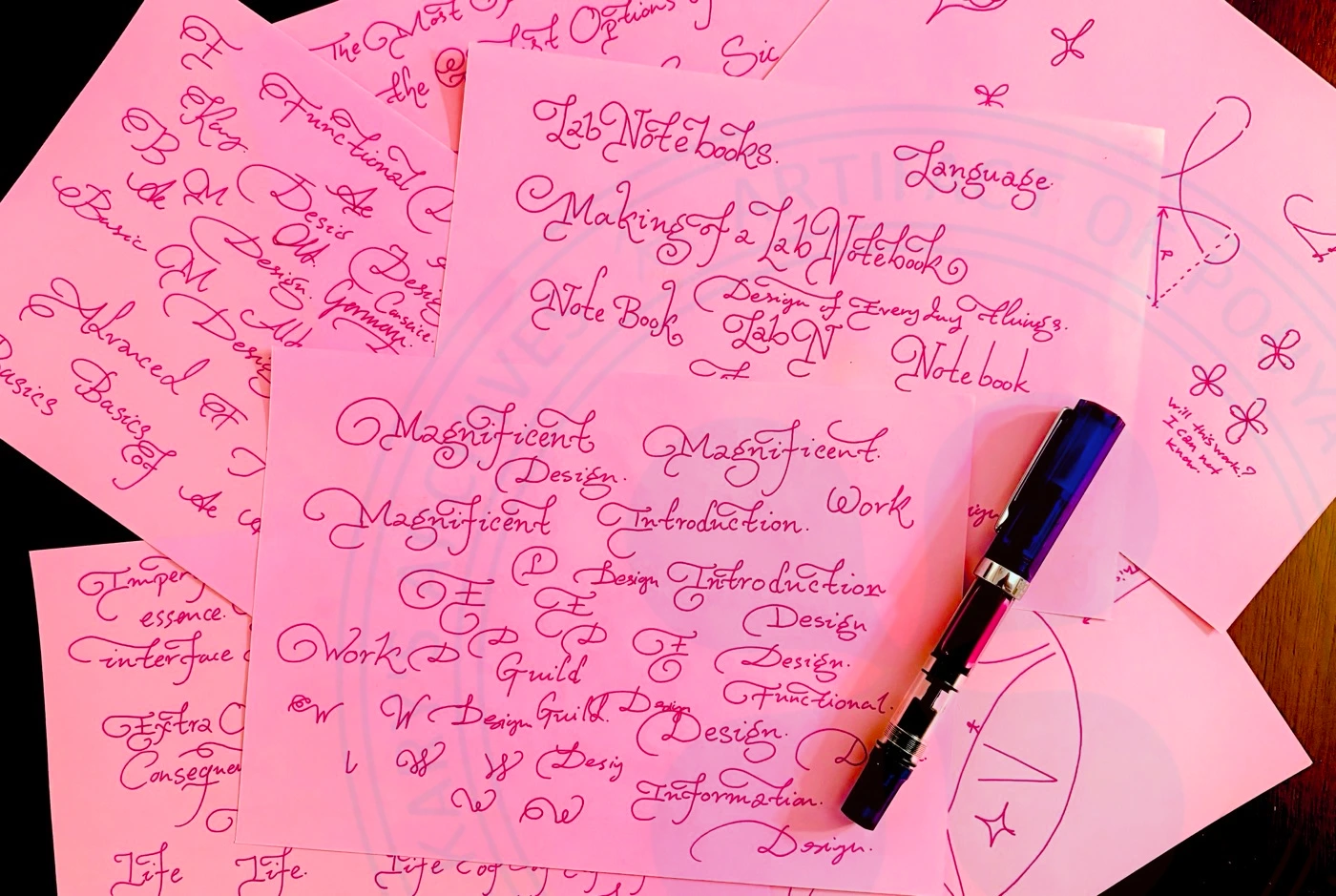

I have been playing around with calligraphy for a few days now. I think I have lost my sense of it, and wish to fix it. (1/1)

The real core value of Japanese culture (or one of them) is something like "never stand out or make a fuss". Nowhere in that principle is a strict requirement to follow the rules. In fact, it's perfectly fine, in Japan, to break the rules as long as that's what everyone does and expects you to do. In terms of framings, the Japanese culture has acquired—by arbitrary and unimportant means—a definition of the concept of (or a "black box" for) "standing out" that differs from its equivalent in many other cultures: instead of being generally neutral, it is seen as intrinsically unpleasant and embarrassing.

The behavior that stems from employing this ontological "thing" (this particular flavor of "standing out") in your mental models is what you see manifested on the train platforms, on the escalators, etc.

The Italian culture has the concept of simpatia that translates awkwardly to English as "being a mix of likeable and/or charming and fun to be around" and doesn't even exist in Japan. I do believe that having this compact and convenient idea of simpatia makes Italians more conscious of the importance of being simpatico and seek that property in others. It drives their behavior in more or less explicit ways.

What I'm talking about is not a unification of actions but of the thinking patterns from which those actions arise. Culture is the mass-synchronization of framings.

A mental model is a simulation of "how things might unfold", and we all build and rebuild hundreds of mental models every day. A framing, on the other hand, is "what things exist in the first place", and it is much more stable and subtle. Every mental model is based on some framing, but we tend to be oblivious to which framing we're using most of the time (I've explained all this better in A Framing and Model About Framings and Models).

Framings are the basis of how we think and what we are even able to perceive, and they're the most consequential thing that spreads through a population in what we call "culture".

Those miraculous scenes have nothing to do with the Japanese DNA: it's their culture. And culture is, by and large, random, arbitrary, and self-reinforcing.

In programming languages, a delimited continuation, composable continuation or partial continuation, is a "slice" of a continuation frame that has been reified into a function. Unlike regular continuations, delimited continuations return a value, and thus may be reused and composed.

Baloney Detection Kit

Wherever possible there must be independent confirmation of the “facts.”

Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view. Arguments from authority carry little weight — “authorities” have made mistakes in the past. They will do so again in the future. Perhaps a better way to say it is that in science there are no authorities; at most, there are experts.

Spin more than one hypothesis. If there’s something to be explained, think of all the different ways in which it could be explained. Then think of tests by which you might systematically disprove each of the alternatives.

Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours. It’s only a way station in the pursuit of knowledge. Ask yourself why you like the idea. Compare it fairly with the alternatives.

See if you can find reasons for rejecting it. If you don’t, others will. If whatever it is you’re explaining has some measure, some numerical quantity attached to it, you’ll be much better able to discriminate among competing hypotheses.

What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations. If there’s a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work (including the premise) — not just most of them.

Occam’s Razor. This convenient rule-of-thumb urges us when faced with two hypotheses that explain the data equally well to choose the simpler. Always ask whether the hypothesis can be, at least in principle, falsified…. You must be able to check assertions out. Inveterate skeptics must be given the chance to follow your reasoning, to duplicate your experiments and see if they get the same result.

Once a self-sustaining feedback loop has started, how it started ceases to mean anything. Mindless forces emerge that suck you in a specific direction.